Inventor of the Spectacle Frame

The introduction of the eyeglass is commonly associated with the Venetians, who created convex magnifying lenses in their famed Murano glassworks in the late 13th century. The process of making the crystal-clear glass was a closely guarded secret and, for a time, anyone trying to leave the Murano islands to share the formula would be sentenced to death... which proved to be an effective deterrent.

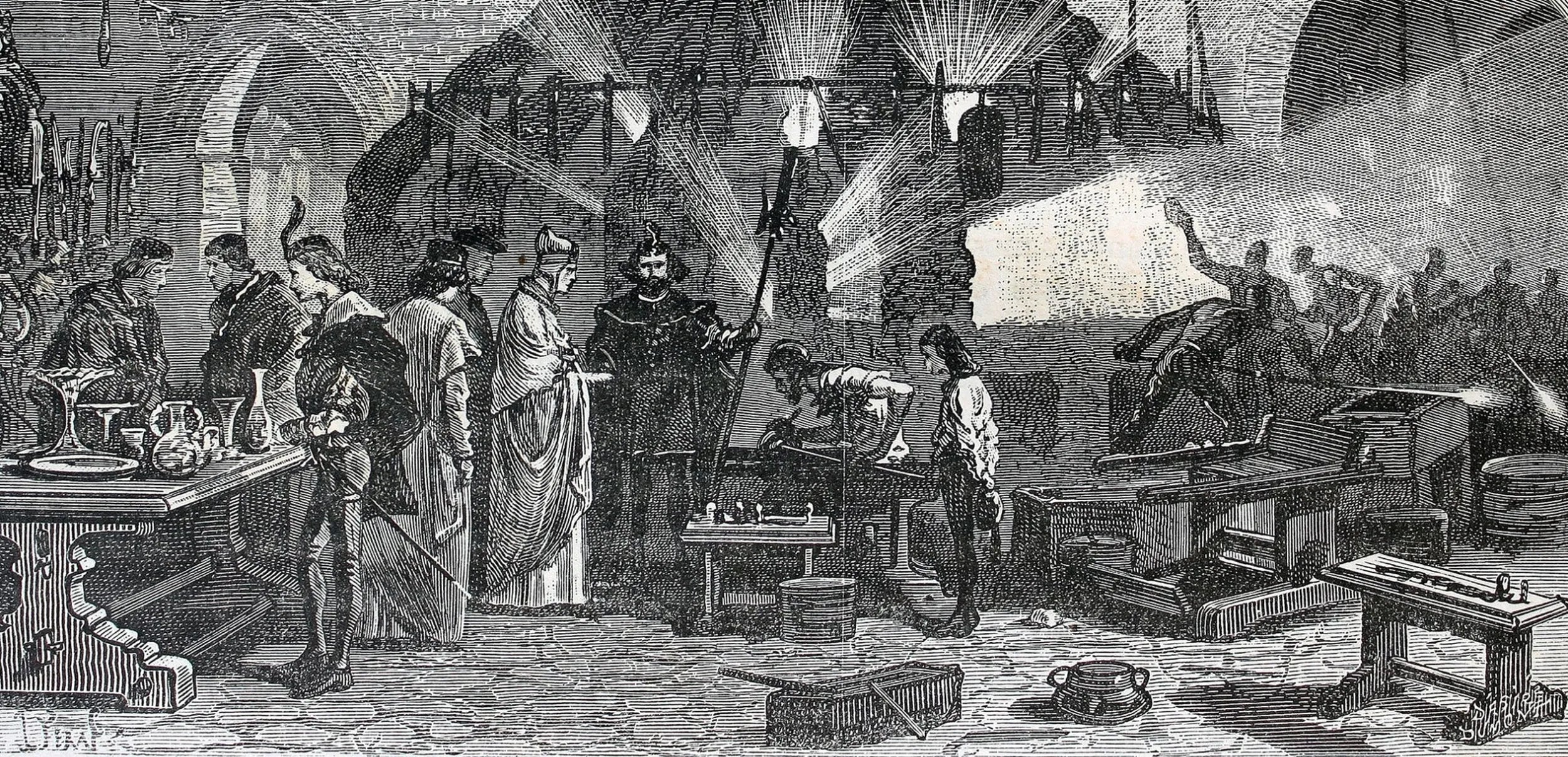

The Doge visits the Murano glassworks

Originally used as "reading stones" that would be placed directly onto manuscripts to enhance their legibility, the visual aid evolved into a smaller lens that could be framed in wood, leather or horn, and held in front of the eye as either a single lens, or paired in a frame with a "rivet" hinge that could be carefully perched on the nose. The earliest depiction in art of these reading glasses was painted by Tommaso da Modena in 1352, in a fresco at the Basilica of San Niccolõ in Treviso.

The first depiction of the magnifying glass and rivet-frame (1352)

Eventually, the Italians lost their monopoly on the production of optical lenses, and the industry spread throughout Europe. In 1705, English optician Edward Scarlett opened 'The Old Spectacle Shop' on Dean Street in the Soho district of London.

Early Ed. Scarlett Trade Card (Credit: Science Museum Group)

He advertised his service to, "Grindeth all manner of optik glasses", offering a wide range of instruments from microscopes and telescopes, to thermometers and barometers, but his area of specialisation was the production of reading glasses.

18th century Ed. Scarlett marketing material

In 1727, Edward Scarlett (abbreviated to Ed.Scarlett in his newspaper advertisements at the time) made a breakthrough that was to forever change the world of optics. Whilst his contemporaries had attempted to stabilise the balance of spectacle frames on the nose by adding devices such as hooks and chains that could be secured to hats and wigs, Scarlett introduced short, hinged arms that pressed against the patient's temples.

Edward Scarlett bridge-frame (middle) and temple-frame (top) c.1727.

The arms of spectacle frames have since, in English-speaking countries, been referred to as “temples”. The snail-shaped temple-tips of Scarlett’s original design were later replaced by hoops on longer temples, through which a ribbon could be passed and tied behind the head. This arrangement was well suited to the fashions of the early 18th century, when wigs covered the ears and made alternative fittings impractical. As wigs fell from favour later in the century, and natural hair left the ears exposed, spectacle makers introduced temples that curved to hook securely behind them — the familiar ear-bend that remains in use today.

18th century optician's workshop (London: 1772)

Almost three centuries later, Scarlett’s simple yet revolutionary idea of hinged temples remains the foundation of modern eyewear. What began in his Georgian workshop in 1727 transformed spectacles from precarious contraptions into comfortable, wearable companions, setting a standard that endures to this day. It was a modest innovation with monumental consequence: a stroke of genius that continues to shape nearly every pair of glasses in the world.

Scarlett's original design (top) and contemporary frame (below)

In 1727, Scarlett’s genius was recognised with a royal appointment as optician to King George II. Nearly three centuries later, it is extraordinary to consider how little the spectacle frame has changed - a reminder that when design is truly innovative, it transcends fashion and becomes timeless.